Introduction

In 1718 King George-I of England became governor of the Southsea Company. The Company was granted a monopoly as it undertook to guarantee the British National Debt. Massive speculation led to stock prices spiralling from GBP100 to GBP1000 within a brief span. Shortly after, the bubble burst to unravel that the chancellor of the exchequer had connived by taking bribes to inflate the stock. Many in British Gentry lost their fortunes, banks failed, directors were imprisoned, and their wealth was confiscated. The outcry that followed 300 years ago was akin to the one we witness today1. As we read the above piece from history, we realize that the reported acts of wrongdoing in the corporate world are not new. The governments’ and policymakers’ responses to the repeated crises have been — the constitution of various expert committees, legislative changes, more stringent rules, and harsher punishments. Amidst the periodic corporate debacles, India hasn’t escaped its share, notwithstanding the ancient wisdom attributed to Chanakya[1], प्रजासुखे सुखं यज्ञः प्रजानां च हिते हितम | नात्मप्रियं हित यज्ञः प्रजानां तु प्रियं हितम || {1.19.34} which means, “in the happiness of his subjects lies the king’s happiness, in their welfare his welfare. He shall not consider as good only that which pleases him but treat as beneficial to him whatever pleases his subjects”.

One outcome of the past few decades was the concept of ‘effective governance’ whereby supervisory Boards monitor and control the Executive (agents) functioning to protect shareholders’ interests.

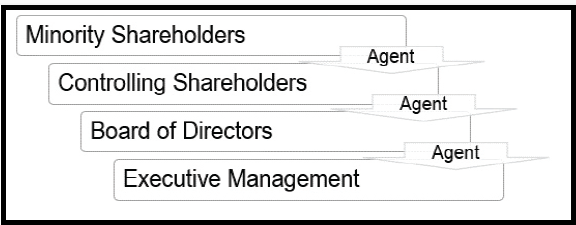

“The directors of companies, being the managers of other people’s money rather than their own, cannot well be expected to watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which they watch their own… Negligence and profusion, therefore, must prevail in the management of affairs of such companies.” The above lines from Adam Smith’s seminal book, Wealth of Nations (1776), which perhaps dominated the psyche of most corporate governance actors, and gave rise to an ecosystem dominated by agency conflict. Further, the increasing complexity of ownership structures and funding made the paradigm of ‘agency conflict’ view not only the Managers as agents of the Boards but also the Directors as the ‘agents’ of shareholders. Further, the controlling shareholders have come to be recognized as the agents of minority shareholders completing the triple principal-agent relationship (refer to the figure). The multiple principal-agent connections thus gave rise to numerous corporate governance rules with Company Secretary as the compliance champion.

Role of Company Secretary as KMP

We were reminded of the 50-year-long journey of the profession when recently, the first generation of company secretaries was celebrated by a website3 by honouring a 100-year-old CS. Over these years, the ‘keepers of secrets’ have earned the goodwill to have privileged access to the backroom theatrics of the Boardrooms and a peep into the executives’ minds. In a profession, where mastering complex issues is a pre-requisite, the Indian CS has acquired humility and the ability to form good relationships. These have become the hallmark of the Indian CS. The Indian law recognizing the CS as KMPs and the sentinels of governance underscore the vitality of their role. The credibility earned by the CS professionals has earned them more respect. Today, as a group of functionaries, they monitor fairness in the multiple principal-agent relationships by checking the rent-seeking tendencies of agents. The early era abilities of administrative expertise and tight-lipped confidentiality are considered hygiene of the profession. Increasingly, in their role as the trusted advisors to the Chairpersons of the Boards, CS guide the principals and agents with their motto सत्यम् वद, धर्मं चर (Satyam vada, Dharmam Chara – Speak the truth, abide by the law; motto adopted at the Golden Jubilee of ICSI).

Agency Conflict and Corporate Governance

One aspect that requires attention is that the corporate governance ecosystem has tended to confine itself to the agency paradigm4 . This is a paradigm that limits the perspectives in dealing with environmental, social, legal, ethical, and behavioural issues pertinent to the modern-day corporation. This is happening in a world where “Corporations dominate all aspects of our lives, affecting the quality of life, food, water, gas, electricity, schools, hospitals, medicine, news, entertainment, transport, communications, environment, and even the lives of unborn babies.”5 The upshot of the realization that corporations increasingly determine the quality of life on the planet, political scientists and society have increased the pressure on businesses to be more responsible and responsive. Under these circumstances, a CS would do better by thinking beyond the agency theory limitations. Therefore, in response to this special issue of CSJ (Rewriting the Rules of Corporate Governance: CG 2.0), we present a few essential multi-theoretical lenses to widen the perspectives.

Lens-1: Stakeholder Theory

To deepen their relationship with the Chairpersons of the Board, along the ‘trusted advisor’6 continuum, the CS must appreciate the breadth of issues confronting corporate governance’s custodians (read Chairpersons and other coalitions of dominant directors & shareholders). The first and foremost is recognizing that the shareholder primacy guiding the corporate governance field is a passé. Fortuitously today’s generation of captains of industry is increasingly aligning themselves to the need of the hour of a ‘stakeholder-centered’ primacy, defined by the choices for the well-being of multiple stakeholders, viz. employees, suppliers, activists, consumers, local communities, and the environment. As the CS cultivate stakeholder thinking, they would be able to remind the actors in the boardrooms of the priority of their obligations to stakeholders over the shareholder returns. Scholars foresee that a theory of stakeholder governance could redefine the field of management in the 21st century, thereby remedying three interconnected business problems7 (i) how value is created and traded, (ii) connecting ethics and capitalism, and (iii) managerial mindset to solve the first two problems. In line with this thinking, CS could influence to re-prioritize Boardroom agendas to develop and implement governance mechanisms for implicit strategic needs and not remain stuck with the tick-the-box priorities. A little proactiveness could bring discussions in the boardroom to recognize stakeholders and factor them into their choices and decision-making.

Lens-2: Resource Dependency Theory

Several global studies have established that a company’s ability to operate under an environment of complexity is directly related to the quality and effectiveness of the ‘board capital,’ i.e., the directors who make up the Board. By managing a company’s external and internal environments, a good Board reduces uncertainty and improves overall efficiency. Perhaps in the past, the Boards were filled with public figures who had exhausted their career run and had some time to spare to occupy ornamental positions or ceremonial roles. Today the reality is different. The directors are more conscious of reputational and other risks. They take their tasks more seriously than ever before. They meet longer, dig deeper, and demand more detailed and better information in terms of quality. Acting in good faith, they try to keep themselves sufficiently informed, exercise due care in oversight, uncover the systemic risks, and require insightful information. The promoters/ controlling stakeholders seek out a diverse range of individuals to collaborate with the CEO, bring fresh perspectives, develop new business strategies, and aid their decision-making. In other words, directors’ compliance oversight job is only a hygiene aspect; they are brought in as a resource to genuinely add value to the Company. Therefore, appreciating the resource dependency lens will help CS understand the skills, knowledge, and expertise required in their Boardrooms. Cultivating this lens will make CS an active advisor while their Nomination and Remuneration Committees (NRC) select new Board members. In an era where professional agency referred candidates, are replacing past familiarity as a qualification to be a board member, this lens will help the CS to: (i) become resourceful in spotting the Board talent (ii) equip their companies to balance board composition, and (iii) help mitigate the myriad contingencies of a fast-changing world.

Lens-3: Institutional Theory

The twin realities of the modern-day corporation, (i) small tenure for which shareholders stay invested and (ii) the shrinking term of CEOs/ Top Management Teams, have put the institutionalization process at risk. Increasingly, the Boards provide institutional resilience to the companies. The Board structure, functioning mechanisms, relationships within & outside the Board, processes adopted for oversight & direction, and their Directors’ use of knowledge and skills increasingly become the cornerstone of a Company’s culture and institutionalization process. Due to ignorance of the institutional lens, CS have often succumbed to the Executive pressures and been solely guided by the Executive, even on matters where the entire Board should have had a primary say. The institutional paradigm reminds the fraternity of CS that their role as the KMPs is to be the scaffolding for organizational resilience. The structure of the Board of Directors and attendant processes which give rise to the schemas, norms, and routines guiding the upper echelons’ behaviour are in the CS’s custody. The CS usually has the final word on how different institutional elements are created, diffused, and adopted. The CS can influence a boardroom debate on the appropriate theme when they notice a decline in the institution-building processes, thereby attempting the stability and order in the sociocultural & sociotechnical aspects of a Board’s functioning and the long-term sustainability of the firm.

Lens-4: Stewardship Theory

To transition to CG 2.0, the CS in India must embrace a fourth lens, that of the Stewardship role of the Board. Agency theory arose from the economic approaches depicting agents as individualistic, opportunistic, and self-serving. As opposed to this, the stewardship theory draws upon the sociological and psychological processes which assume the agents as collectivists, pro-organizational, and trustworthy, thereby reposing a belief in agents that they work in the best interests of their principals. We must recognize that just as a CS is associated with professional bodies that provide ethical guidelines and codes of conduct, the BoD, too, are guided by professional ethics. Unlike the agency lens, which would tend to attribute that agents (Directors/ Executives) would work in their self-interest, the stewardship lens recognizes that individuals have their aspirations of ‘reputation’ and contribution to the well-being/ betterment of stakeholders’. They are inclined to make decisions in the organization’s long-term interests due to their intrinsic motivation (and not solely due to extrinsic rewards). It helps to unify the objectives of the CEO and Chairperson.

Conclusion

The Agency Theory as the sole guide-post and the associated stringent corporate governance controls have had limited success in (i) preventing corporate collapses or (ii) enhancing the trust quotient between the multitiered principal-agent relationships. The socioeconomic, geopolitical, and ecological concerns have put new pressures on the sustainability of enterprises. The existing paradigm and approaches are proving insufficient even to contain even the agency costs leading to a demand for a more holistic approach. As the Governments, Companies, Boards, and Executive Management pay attention to the neo-voices and emergent issues confronting the corporate world, one thing is clear, the slavery to agency paradigm is set to end soon. The new corporate governance practices are likely to rise above the din of shareholder capitalism. Under these circumstances, the Company Secretaries can enrich their perspectives through the four lenses provided above. The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized that the stakeholders value companies’ health over shareholders’ wealth. The activist investors, institutional advisors, and voices in Annual General Meetings about dividend determinations, “Say on Pay” resolutions, and the (re)appointment of directors are symptoms of more structured attention demanded by stakeholders. The supply chain breakdowns, travel restrictions, IPR for pharma companies, lockdown & their impact and the debates between lives and livelihoods have increased the microscopic gaze on how businesses interact with society. Amidst this scenario, the multi-theoretical perspectives will help a Company Secretary widen his/ her scope of attention and recognize the wide-ranging causes and effects impacting their Board decisions. Such comprehensive perspectives equip a CS to move up the continuum of being a trusted advisor. Be it a need to influence their promoter-shareholders, chairpersons, CEOs or other directors, the multiple theory lens widens the repertoire of knowledge. A high-octane Company Secretary will appreciate that pivoting good governance not only requires tact & diplomacy and procedural mastery but also perspectives and knowledge far beyond what we have learnt from the agency theory zealots.

1. 2005 Ticker Bob, “Corporate Governance – Principles, Policies and Practices” third edition

2. Arthshastra (circa 400 BC – 150a AD) an ancient Indian text that many scholars have argued to be the earliest corporate governance treatise

3. https://sharadasc.com/100-year-young-company-secretary-mr-v-k-murti/

4. We discovered this a survey on Board Evaluation practices, two years ago.

5. Mitchell, A.V. and Sikka, P. (2005) Taming the corporations.

6. The classic book Trusted Advisor offered a four step journey in depth of relationship

7. Freeman, R.E. et al. (2010) ‘Stakeholder theory: The state of the art’, Management Faculty Publications Univ of Richmond, 99, pp. 1–57